Tree Vulnerability to Climate Change

Tree Vulnerability to Climate Change- Water Connecting Space and Time

- LTER Network Collaboration

- The Forest during COVID-19

- New Support for Ongoing Work

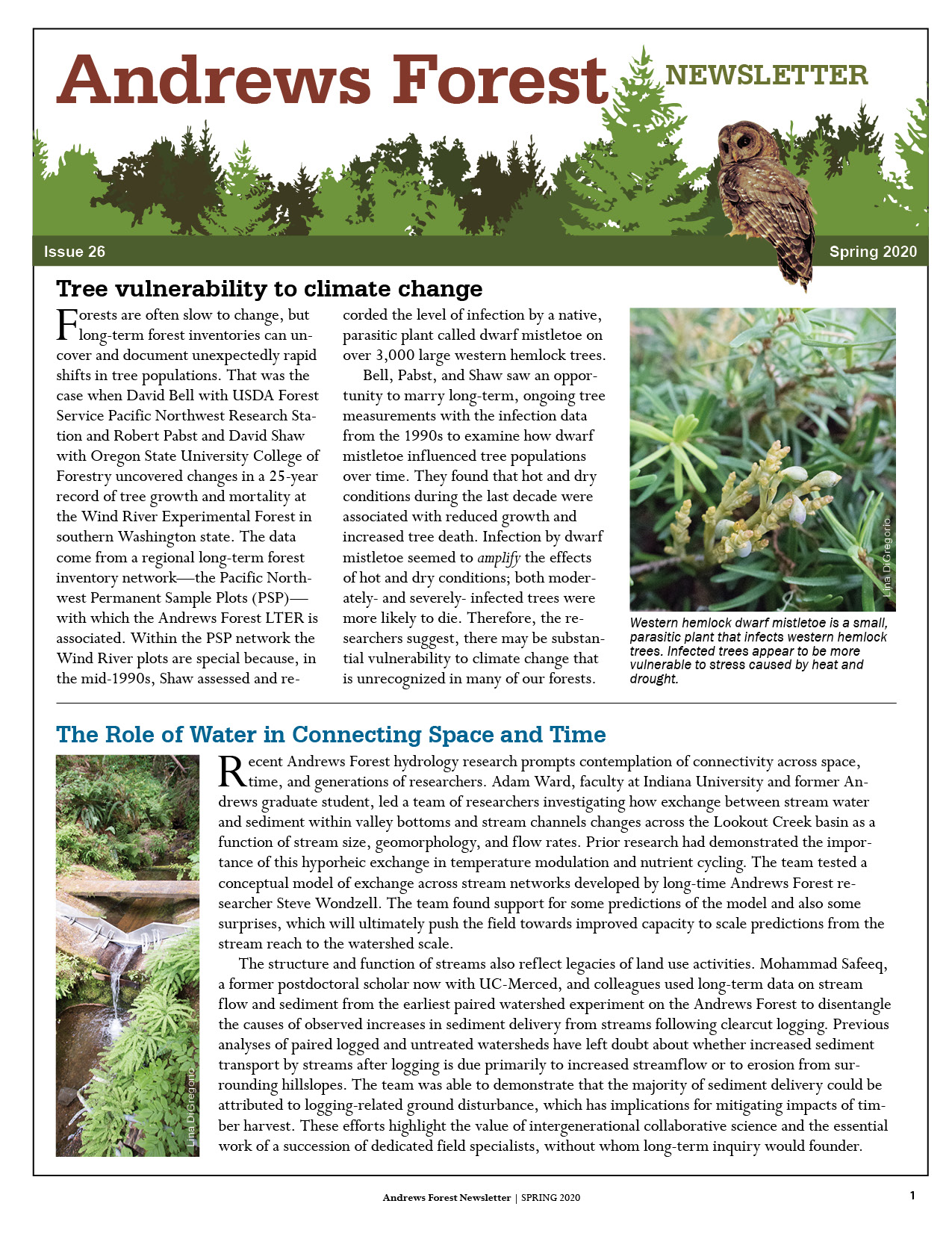

Forests are often slow to change, but long-term forest inventories can uncover and document unexpectedly rapid shifts in tree populations. That was the case when David Bell with USDA Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station and Robert Pabst and David Shaw with Oregon State University College of Forestry uncovered changes in a 25-year record of tree growth and mortality at the Wind River Experimental Forest in southern Washington state. The data come from a regional long-term forest inventory network—the Pacific Northwest Permanent Sample Plots (PSP)—with which the Andrews Forest LTER is associated. Within the PSP network the Wind River plots are special because, in the mid-1990s, Shaw assessed and recorded the level of infection by a native, parasitic plant called dwarf mistletoe on over 3,000 large western hemlock trees.

Bell, Pabst, and Shaw saw an opportunity to marry long-term, ongoing tree measurements with the infection data from the 1990s to examine how dwarf mistletoe influenced tree populations over time. They found that hot and dry conditions during the last decade were associated with reduced growth and increased tree death. Infection by dwarf mistletoe seemed to amplify the effects of hot and dry conditions; both moderately- and severely- infected trees were more likely to die. Therefore, the researchers suggest, there may be substantial vulnerability to climate change that is unrecognized in many of our forests.

Full article: Bell, David M.; Pabst, Robert J.; Shaw, David C. 2019. Tree growth declines and mortality were associated with a parasitic plant during warm and dry climatic conditions in a temperate coniferous forest ecosystem. Global Change Biology. 00: 1-11. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14834

Recent Andrews Forest hydrology research prompts contemplation of connectivity across space, time, and generations of researchers. Adam Ward, faculty at Indiana University and former Andrews graduate student, led a team of researchers investigating how exchange between stream water and sediment within valley bottoms and stream channels changes across the Lookout Creek basin as a function of stream size, geomorphology, and flow rates. Prior research had demonstrated the importance of this hyporheic exchange in temperature modulation and nutrient cycling. The team tested a conceptual model of exchange across stream networks developed by long-time Andrews Forest researcher Steve Wondzell. The team found support for some predictions of the model and also some surprises, which will ultimately push the field towards improved capacity to scale predictions from the stream reach to the watershed scale. https://www.hydrol-earth-syst-sci.net/23/5199/2019/

The structure and function of streams also reflect legacies of land use activities. Mohammad Safeeq, a former postdoctoral scholar now with UC-Merced, and colleagues used long-term data on stream flow and sediment from the earliest paired watershed experiment on the Andrews Forest to disentangle the causes of observed increases in sediment delivery from streams following clearcut logging. Previous analyses of paired logged and untreated watersheds have left doubt about whether increased sediment transport by streams after logging is due primarily to increased streamflow or to erosion from surrounding hillslopes. The team was able to demonstrate that the majority of sediment delivery could be attributed to logging-related ground disturbance, which has implications for mitigating impacts of timber harvest. These efforts highlight the value of intergenerational collaborative science and the essential work of a succession of dedicated field specialists, without whom long-term inquiry would founder. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2019.124259

In my nearly eight years as Lead PI, I have never written (nor have you read) a “letter from leadership” in such strange and rearranged times. The lives of people in our community are disrupted, we are learning to live with and school our own children, we are feeling disoriented and unproductive, we are tensely anticipating sickness and death in our personal worlds, we are worried about family and loved ones but unable to be with them and express our love personally. And of course, we are worried about how this pandemic will impact our work, our professional lives, our research. Though talk of “silver linings” seems tone-deaf, a crisis can create opportunities. The covid-19 pandemic offers some potentially important opportunities to newly understand not only the ecological impact of our profligate ways of life, but something also about how the world might heal when the press of humanity is eased a bit. It also offers us an opportunity to reexamine our work and our community. It affords us an opportunity to relearn important virtues (compassion, support, patience, kindness, humility, caring) and to tamp down some of the less meritorious tendencies (competitiveness, pettiness, control and power grabbing, hubris) that are sometimes sadly rewarded in our professional lives and become habits. Perhaps most importantly, it presents counter evidence to dogmatic assertions about what humanity can do, what we are capable of, when called to action. In the midst of all of the chaos of the day, I would ask each of you care for yourselves, to care for those you love and those you don’t even know, and to take some time to reflect on what this crisis might mean for you and your work going forward. And, most importantly, please please be careful.

Stephen Calkins is a Master’s student in Forest Engineering, Resources, and Management at Oregon State University, working with Dave Shaw as his advisor. Calkins’ research explores how canopy structure and sapwood of old and mature western hemlocks are transformed by infection by western hemlock dwarf mistletoe. He spent the summer of 2019 at the Andrews Forest climbing and intensively measuring the canopies of 16 hemlocks along an infection severity gradient from uninfected to totally infected, measuring every branch, mistletoe infection, and taking multiple tree cores. Calkins is modeling the impacts of mistletoe infection using three metrics to produce the first set of detailed relationships for old and mature hemlocks. Mistletoe intensification resulted in a compaction of the tree crown, reduction in foliage, and increase in dead branches, although relative sapwood area appeared unaffected. Further analysis will expand our understanding of how this important parasite in shaping canopy structure. See more photos of the dwarf mistletoe survey.

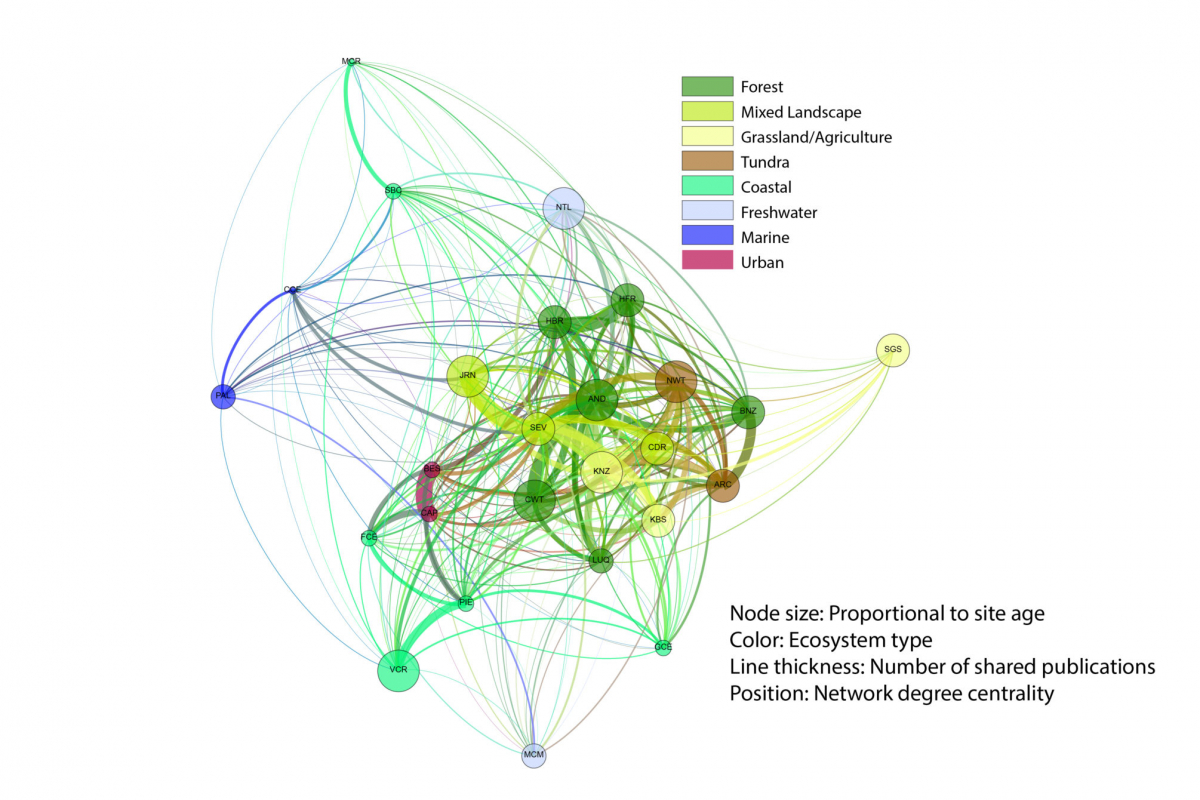

In its 40-year history, the LTER Network has valued inter-site projects to learn ecological principles that pertain not just at site- or ecosystem-scales, but across the continent. A recent study reveals patterns of the intensity of collaborations across the network. Analysis of LTER collaborative science against a sampling of the general ecological literature finds more collaborators from more institutions and more persistent collaborations in the LTER community. Early LTER emphasis on open data sharing and synthesis of ecological patterns across ecosystems types likely facilitated the development of this highly connected network structure. See the LTER Network Office's newsletter article and the full article, "Collaboration across Time and Space in the LTER Network."

As we navigate the COVID19 pandemic we hold the health and safety of everyone involved, including those in surrounding rural communities, as our top priority. After that, we prioritize our long-term measurements requiring continuous records, and finding ways to facilitate success of graduate students and others on constrained timelines. It is possible that long-term records will provide valuable context about how regional and global changes in human behavior can be seen in our ecosystem. Many of the research projects at the Andrews Forest have a focused field season in the spring or summer. Those projects are being delayed, canceled, or retooled. Developed hiking trails across the Willamette National Forest are closed, and Andrews Forest headquarters facilities are closed to all visitors, including researchers.

Over the decades, the Andrews Forest program has been party to some history making. Now, several motivations are prompting reflections on the historical legacies of early research that continue to reverberate in science and policy today. Forest Service scientist Tom Spies, who has been an important contributor to Andrews Forest science, recently lead a review of the scientific literature (Twenty‐five years of the Northwest Forest Plan: what have we learned?) published in the 25 years since the Northwest Forest Plan (NWFP) went into effect in 1994 to guide management of 10 million hectares of federal forests. Research rooted in the Andrews Forest on topics such as old growth, northern spotted owls, and forest-stream interactions influenced the NWFP. Andrews Forest-based science on these topics has continued; and relevant, new science is proposed in the LTER8 grant under review. Ongoing and newer science will be an integral part of the NWFP revision, now underway.

The role of large wood in streams has been a feature of Andrews Forest science since the mid-1970s, and helped seed a global expansion of work on the topic. Andrews Forest scientists were present at the fourth international conference on Large Wood in World Rivers IV in Valdivia Chile in 2019 and co-authored a state-of-the-science paper (Reflections on the history of research on large wood in rivers) from the conference. That paper synthesizes a century of progress in the study of large wood in rivers for a host of objectives, such as ecosystem science and management, protection of human communities and infrastructure in mountain landscapes, and roles in global carbon dynamics.

What does a Professor of Catholic Theology and Culture find when immersed in an ancient forest? Theologian and Andrews Forest writer-in-residence Vince Miller writes about Pope Francis’s encyclical Laudato si’, translated as “on care of our common ground” or “integral ecology”:

“Pope Francis offers a vision of moral responsibility rooted in awareness of the world around us. He writes of an ‘attitude of the heart, one which approaches life with serene attentiveness, which is capable of being fully present’ to everyone and everything. And he also calls for an ‘intense dialogue’ between religion and science, which has its own ‘gaze.’ The H. J. Andrews Experimental Forest in Oregon, one of the world’s most studied ecosystems, offers an especially rich opportunity for such dialogue. Here scientists have cultivated their own gaze of ‘serene attentiveness.’ What can theology learn by looking with scientists at such a complex ecosystem?

“Pope Francis offers a vision of moral responsibility rooted in awareness of the world around us. He writes of an ‘attitude of the heart, one which approaches life with serene attentiveness, which is capable of being fully present’ to everyone and everything. And he also calls for an ‘intense dialogue’ between religion and science, which has its own ‘gaze.’ The H. J. Andrews Experimental Forest in Oregon, one of the world’s most studied ecosystems, offers an especially rich opportunity for such dialogue. Here scientists have cultivated their own gaze of ‘serene attentiveness.’ What can theology learn by looking with scientists at such a complex ecosystem?

Entering an old-growth forest can be overwhelming. The sheer, tangled abundance of life is shocking. If John Muir was right to describe these as ‘cathedrals,’ they are messy and riotous ones.”

Miller delves deeply into the forest, drawing on his own gaze, science-inspired stories, and the images and writing of photographer David Paul Bayles, to create a moving, illustrated essay “A Cathedral Not Made by Hands” that appeared in the Catholic journal Commonweal.

Gifts to the Andrews Forest have meaningful and positive impact on our ability to carry out our mission to support science, education, and humanities activities at the forest. We are excited to share and celebrate two recent gifts benefitting the Andrews Forest.

A $500,000 gift from generous donor has created the new H J Andrews Environmental Education Endowment to “educate youth in environmental stewardship at the Andrews Forest.” The income from this endowment will support outdoor learning experiences such as Canopy Connections, Season Trackers, Discovery Trail Programs, and Ellie’s Log and Supplemental Teaching Materials. These programs, at the core of the Andrews Forest K-12 education efforts, have been sustained for years in part by annual gifts from private donations. The establishment of the permanent education endowment will provide continual support, making it possible to plan ahead and sustain our relationships with teachers and schools well into the future.

We are also excited to share that an anonymous donor gifted $50,000 to the H J Andrews Experimental Forest Endowment, creating a lasting impact and increasing our ability to support science, education, and humanities activities.

Gifts of all sizes to these endowments make the long-term work we do possible, today and well into the future. Support of the Spring Creek Project also fuels Ecological Reflections, an arts and humanities program at Andrews Forest.

Learn more at andrewsforest.oregonstate.edu/donate